Cleveland Topics, July 1, 1916

Cleveland Sculptors at Work

Joseph Motto and Stephan Rebeck, sculptors, clad in the art uniform of canvas coat, which somehow appeals more to me than does the military khaki, were busily fashioning from plastic clay their quaint conceptions, when I stopped at the studios at 11634 Euclid avenue.

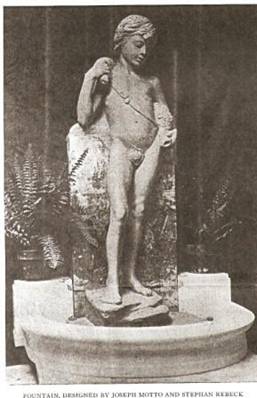

One of their newest things, just cast in plaster, is “The Wave,” and for rhythmic, poetic beauty it surpasses, I think, anything else they have done. It is intended as a fountain, and will be exquisite in gold-glinted bronze, the backward-swaying figure, water swathed, the real water jetting from fishes’ mouths and dancing in the light.Another new work is Pan, playing his pipes, Pan the ever-popular: and like every other creation of these young sculptors, whether old or new in theme, it is done in a new way. Other works are: Their water-bearer fountain, shown at the Builders’ Exposition at the Wigmore Coliseum; their fountain of a boy with a butterfly, bought by Mrs. John Newell, a plaster cast of which was shown at the Flower Show; a wall fountain, ten feet high, made for the Hydraulic Pressed Brick Company, in the pressed brick, to demonstrate the adaptability of brick in sculpture; a bust of F. Ward, superintendent of the Brotherhood Club; a plaster panel for this club, adorned with the figure of an angel, in the shadow of whose wings two men clasp hands, and bearing the inscription, “To Thine Own Self Be True;” while they have just finished a model for a new setting for the Perry cannon in the Public Square, to be used when the cannon is transferred to the new City Hall, the base to be in granite, while the flag draping the cannon will be in bronze.

Their boy astride his turtle-steed has a face that brims with fun; the grin of their Bacchus is delightfully diabolical, if you will pardon the adverb, no other could express just the same shade of meaning; there is a fine figure of Kosciusko, and portraits bas-relief of several Cleveland boys.

Among the photographs of old-time things, through which we ransacked, was one of a study made in the sculptors’ school days, a man lounging in his chair, the face tired physically, yet shadowed, too, with troubled thought. I think I have never seen in sculpture such relaxation so easily expressed in every line, nor a face so true-to-life in keeping with the posture.

“What have you done with that?” I asked, “You should have had that cast in bronze as an ornament for some man’s den.”

“That was destroyed long ago, with other school studies,” said Mr. Rebeck. “We leave many things unfinished. We have not tried to commercialize our work; we work mostly for our won pleasure. Our studio is in an out-of-the-way place; very likely many think of it as a stone-cutter’s shop. But we don’t expect fame,” smiled Mr. Rebeck, “no sculptor or artist need look for fame while he is living.”

“We might do as Rembrandt did,” suggested Mr. Motto, “go away for a period, and let our friends circulate the report that we have died, and auction off our stuff at fabulous prices!”

“Or you might enlist and get shot by a Mexican as a martyred sculptor-hero!” quoth Mr. Rebeck.

“I sometimes think I would like to enlist,” said the other, “but I am too short.”

“Well, shortness has its disadvantages; for instance, in such work as ours, it is a hindrance. But, speaking of enlisting, I saw an ‘ad’ headed ‘Chance for aviation;’ I told a fellow who wanted me as a recruit that I would go if I could go in the Aviation Corps. But he scowled at me and said, ‘Stop your kidding!’”

“You always did aspire to higher things,” commented Mr. Motto, at this juncture. “But if we were to coat a piece of sculpture with gold leaf, put it in a case and station guards on either side of it, people would fall over themselves to buy it, you know,” said Mr. Rebeck. “It’s all in the way you advertise. But we are dreamers.”

“Yet we must dream before we can create, you know that,” was Mr. Motto’s response.

And so they work merrily, yet thoughtfully, these two young men chiseling Today their own niche in Tomorrow.

Both are small in stature, yet there is the contrast that marks congeniality: Motto is a dark-eyed idealist; Rebeck is blued-eyed and practical.

Both graduated under Herman N. Matzen three years ago; and hardly a day goes by that Mr. Matzen does not look in at the studios to note their progress; while, like every other pupil of Cleveland’s master sculptor, they do him homage in affection and esteem for the man as well as the artist. They were Mr. Matzen’s helpers on the Tom L. Johnson memorial.

As soon as they can secure a suitable building they will move nearer the downtown section of Euclid avenue, that their studios may be more accessible to the public.